As a priest, I spend a fair amount of time around people who are dying. Whether in a hospital or at home, it’s a common part of my duties to bring people the sacraments in such situations, to hear their confessions, to anoint them, and, if they are able, to give them viaticum, the Blessed Sacrament one last time. And often these encounters can be truly beautiful, as it’s a great privilege to be able to accompany a Christian soul as it prepares to leave this life and go to meet our Lord.

Yet sometimes these encounters can also be painful, and not just because of the human anguish that is nearly always involved when someone dies. Because it is not infrequent, tragically, that in talking to the families of someone who has just died or who will soon die, that the family will say something like, “Our mother didn’t want to have a funeral” or “Our father is going to be cremated, and if we do a funeral mass, we’ll do it in six months so that it’s easier for people to travel in,” or “What we really want to do is simply to celebrate our grandmother’s life.”

And on a certain level I can understand why people say these things. Usually they’re said out of a desire not to be a burden or not to make a fuss. But then, upon a moment’s more reflection, does that not make it all the more tragic? To be a burden to others is simply to be human, and to love someone is, among other things, to bear that person’s burdens, and to allow ourselves to be loved is to allow ourselves to be a burden to others. Or, again, sometimes these sentiments arise out of a reluctance to face the reality of death, either in the moment or afterwards – for which reason people even often fail to call for the priest until it is too late and the person has already died. But this fear, though understandable, does not keep anyone from dying, though it often does keep people from dying well.

But perhaps worst of all, this reluctance that people have to call for the priest or to have a funeral mass, or to delay the funeral mass beyond all reason, reflects a failure to take the faith seriously, a failure to live in reality. Because this is the reality: when you die, you are not annihilated. As we will hear in the preface to the eucharistic prayer, at death life is changed, not ended. And assuming then, that you have not ultimately rejected Christ, and thereby find yourself among the elect, what will you experience? If you were in bodily pain, you may find that all of this is taken from you an instant, and if you were unconscious, you will find yourself suddenly come to awareness. And in this new awareness, you will find that you are not quite yourself – you will have no body – no eyes with which to see, no ears with which to hear – and yet you will be able to see, more clearly than you ever have before, the presence of the One, the Eternal Word, He who is Goodness, Beauty, and Truth itself, present to you with an unimaginable immediacy. And this will indeed be wonderful, but it will also be, for most of us, intensely painful as well, like looking straight into the sun. Because most of us, when we die, are not yet purified so as to be able to receive that blessed vision. We die with our attachments to this world still intact, whether it be an overfondness of drink, a bit of a temper, a touch of vanity, or what have you. And losing all of these things in death, all of these attachments, we will feel that loss as pain, and we will not be able to truly enjoy the vision of God until those worldly attachments are taken from us, burned away in the purifying flames of Purgatory.

As for what exactly that purification will look like we can only speculate, but we can at least say that it is not something that will be achieved by our own efforts, not merely because we cannot save ourselves, but also because, being dead and bereft of our bodies, the time for us to win merit by our cooperation with grace will be past. Rather, we will only be able to depend on the merits of the Church offered for us, which is to say that our purification and thus our final entrance into the beatific vision will require the prayers and sacrifices of our fellow Christians who are still living, for thus has God so arranged the economy of our salvation, that we might be reminded of our continued communion with our deceased brothers and sisters in the Lord, and that we might have this opportunity for doing for them this act of charity.

All of this to say: you will want prayers after you die. If your grandmother told you she didn’t want a funeral mass before she died, I assure that she wants one now. If you aren’t planning on having a funeral mass, I can promise you that you will regret that decision the moment that you die, and I hope your family has the good sense to give you a funeral mass anyway. And if you’re hearing this and you’ve been in that situation where a loved one was buried without the prayers of the Church, know that it is never too late to pray for the repose of that person’s soul, it is never too late to ask that a mass be said on their behalf.

And indeed, that is what this feast is for. This is why we’re wearing funeral vestments. For truly it is known to God alone how many souls there are in Purgatory, how many souls there are waiting for our prayers so that they may be purified and enter into divine radiance. And so we must not be lax in fulfilling our Christian duty of charity to these our brothers and sisters, praying for them on this day and throughout this month of November, which is especially set aside for this purpose.

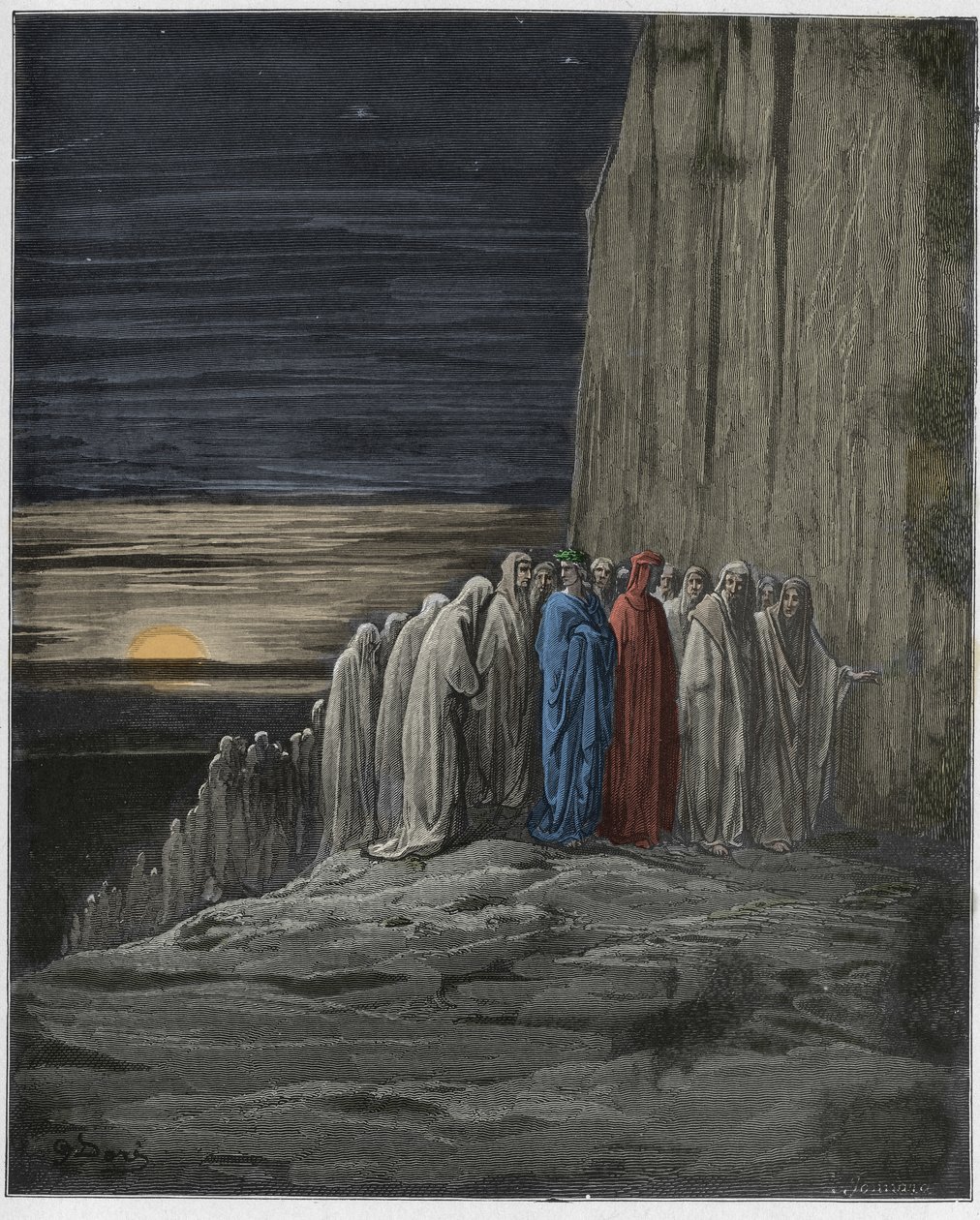

For make no mistake: the veil between this world and the next is more thin than we often imagine. The Church Triumphant in heaven intercedes for us here below, while we, the Church Militant, work out our own salvation here on earth while praying for the Church Penitent in Purgatory. Sometimes we are granted glimpses of this reality – from at least as early as the Martyrdoms of Sts. Felicity and Perpetua we have accounts of Christian mystics being granted visions of this communion – but nowhere is the veil between the living and the dead thinner than it is here at this sacrifice. For the Christ whom we worship in this Sacrament, he is the same Christ as is worshiped and adored both in Heaven and in Purgatory. And so, though we may not perceive it with bodily sight, there is a real sense in which the entire Church is, here at this altar, gathered together, such that when we draw close to Christ in the Eucharist, we draw close also to all of those who have gone before us in the faith. So may we be mindful of this great communion in which we are unimaginably blest to share, never growing slack in our prayers for the purification of all the faithful departed.

Leave a comment